Afternoon jam

The negotiations began; the multi–hour phone calls, the pleas, the promises. Vicki stayed back in Philadelphia for a month. I gave the City of Brotherly Love a new name: Philthydelphia. We finally worked out a compromise; she would come back and the family would be together for Patrick’s birthday, December 9, and for Christmas. After that, Vicki planned to leave; she did not want to live in California any longer. I had three months in which I hoped Vicki would work with me and figure out how to keep our family together. If it meant moving back to Philly, so be it. The climate was suddenly unimportant; the Southern California weather that I loved no longer mattered if it meant losing the girl I loved. How do you know you’re in love? Simple. It’s when you know that no one who ever lived has ever loved this much before, and no one who falls in love will ever love this much again.

Just before Vicki went back east I realized a lifelong dream. I’d loved the game of pool since I was a kid. During my teens I saw Willie Mosconi, pool’s Babe Ruth, play exhibitions five times. I have snapshot memories of each one I will carry forever. I always wanted my own regulation–sized pool table. A friend had one he had to get rid of; his wife wanted a real dining room table. I converted the garage into a game room, moved the Kiss pinball machine from the dining room out to there, purchased a Rolling Stones pinball machine, and the pool table fit perfectly with no interference from the walls that would restrict any shot. It was an antique Brunswick table, the kind with leather pockets. I had it re–covered; the bright new felt made it look magnificent. The game room was completed in early August, just before Vicki made that fateful trip. I played every day until she left; I thought ahead to the fun of teaching Patrick to play the game. I stopped going out to the garage when Vicki said she didn’t want to come back; it just wasn’t fun any longer. Be careful what you wish for…

With Paul taking care of most of the mailing, I spent every possible hour at home with the family. We went to all the places the children loved once a month for the next three months; we went to the places Vicki and I enjoyed four or five nights a week. It was working; I could feel it. I’d adjust to Philadelphia; I’d learn to put up with the cold. Who was I kidding? I hated the cold. I’d learn to shut up about it; that was all I could hope to do. I’d let Paul run things by himself for a while; we’d get back to making albums next year.

Before then, we had the “Million Dollar Quartet” and “The ’68 Comeback Vol. 2” just about ready for release. I finalized things with printers, label makers, and the mailing service and the flyers went out the beginning of November. The albums would be ready before Thanksgiving; they would be arriving in customer’s hands in late November and early December. Just a small cadre of our closest friends knew our plans; we hoped the response would equal what we felt the historic Memphis reunion deserved.

I was paying little attention to any leads on material we might pursue to use for an album; so little, that it took a reminder from Paul to jog my memory. He asked, “Did you ever get a chance to track down Phil Ochs’ brother, the one who is supposed to have a tape of Elvis rehearsing off–camera during the ’68 Comeback days?” I wrote items down so I wouldn’t forget; there were always so many things to do. There it was, somewhere in the middle of my “To Do” list. Copied twice weekly for the last few months as things got scratched out and others added. The beach was a long drive; I had called and spoken to Michael Ochs just once and he said he would have to look around and find the tape. He wasn’t sure where he put it and the house was a mess, with every square inch being used to hold items for a new business venture that was in its start–up stage. That was why I hadn’t actively pursued it; I wasn’t sure if he could actually locate the tape.

I called Michael, he said he found the tape, and we set up an appointment for later in the week. I arrived eager to find out just what he had and if it would be of any use to us. Michael lived in a quaint, roomy old house in Venice Beach that probably dated back to the 1930’s. It had a porch, parlor, pantry, and foyer, ornate cornices, burnished wood floors and moldings, gleaming banisters, and, if you looked closely, cherry and mahogany coffee tables, end tables, sideboard, and dining room table either Queen Anne or Victorian, with magnificent inlay and carving. A Hoosier desk that would fetch a small fortune at auction, and stately leather–covered chairs with claw feet, like those found in English gentleman’s clubs, dominated one corner of the living room. These museum pieces peeked out at me, barely recognizable, for every square inch, every chair, every tabletop, all over the floors, were piles of photos and old newspaper clippings. There were 8 x 10 shots of every group and solo artist I had ever heard of from the 50s, 60s, and early 70s. A few were new to me (and I knew the music from those years as well as anyone, or so I thought); the enormity of the collection was astounding. There were literally tens of thousands of photos, both candid ones and publicity shots. Michael had contacted the newspaper photographers, just as we had done with the 1961 Hawaii concert, and obtained glossy original prints of photos that appeared in magazines and newspapers from all over the country. He also obtained the rights to use these photos; he made deals with photographers to share the royalties in some cases, the others he owned outright.

Michael’s intention was to set up an archive service for newspapers and magazines; whenever they needed an accompanying photo for an article about any rock, pop, or folk act they would come to him and he would have it. If he didn’t have it, it wasn’t available. Over the next decade I saw, “Courtesy Michael Ochs Archives” under virtually every photo that was not a current one in Los Angeles Times stories about musicians in their famed Calendar section. Michael saw a niche market, cornered it, and his photos have graced newspapers and magazines worldwide for many years.

Michael handed me a cassette that was labeled, “Elvis rehearsal.” “What’s on it?” “Just some studio jam session; sounds like it’s from the sixties.” I brought two copies of all our albums for Michael; I even had a test pressing of the “Million Dollar Quartet” and promised to mail him one as soon as it came off the presses. I spent a couple hours looking at all the photos and newspaper snippets; they took me all the way back to Junior High; back when hearts and minds were young and everything was possible. Chuck, Roy, Bo, Jerry Lee, Ritchie, Buddy, they were all there. Another table held Smokey, Marvin, Ronnie, Dylan, Joan, Del, Tommy, and all the friends I graduated with and took to college with me. I could have stayed for days; Michael said I was welcome to peruse as long as I liked and to come back anytime. I took my leave, started the drive back to Glendale, and ten or fifteen minutes went by before I slipped the cassette into the slot on the dash. I had other things on my mind; racing home from Brian’s record store seemed like a long, long time ago.

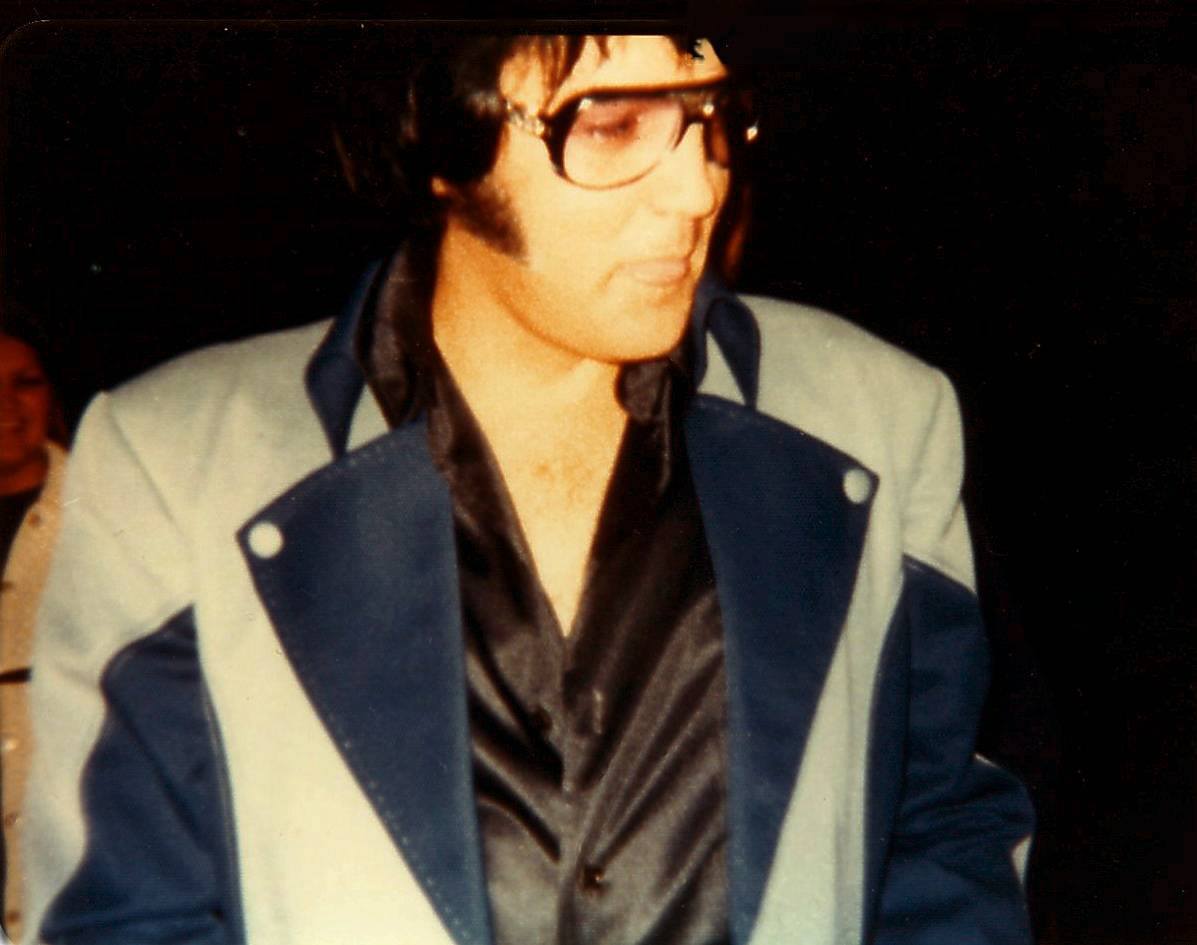

The tape was something special: raw and informal, just a bunch of people having a good time. One of them happened to be Elvis Presley; that boy could sing. There were a few lines from some of the fifties big hits: “Young Love” by Sonny James was a part of growing up for kids my age. “Oh, Happy Day” was a smash by the Edwin Hawkins Singers in the sixties. These were songs I would have loved to hear Elvis do all the way through. Then he launched into a bold, brassy version of “When It Rains, It Really Pours.” Hilburn confirmed. The kid could sing anything he wanted to: blues, gospel, pop, country, or rock. He had it all and he’d been gone for over three years now. He gave us over twenty years of his song mastery; we’d have settled for a hundred more.

I shipped the tape to Paul; we had another album just like that. We would do another double release to start off the new decade: “Afternoon Jam” and “The Valentine Sessions” were in the can. We’d find pictures and do liner notes after the holidays.

Things were going wonderfully between Vicki and I; I couldn’t see how she could possibly leave. We’d all go back east together next year; we’d find a house in Philadelphia and start over. Patrick had just started first grade and it was important that he finish the year where he started. This was a formative moment for him; Vicki wouldn’t do anything to mess that up.

I spent the necessary days finalizing everything for our two new albums and making sure Waddell had all the covers and labels they would need. Flyers and catalogues were sent, wholesale orders readied, and I did my darndest to see that everything ran without a hitch. Supervision of Robert and Glen was at a minimum; I spent as much time as I could at home or out someplace with the family. I even let Robert pick up the film and videotape orders, solely my domain until now, but the orders were not sealed and shipped until I checked them. There was too much money involved with those items; the reason things ran so well was that I made sure they did. Giving up control was difficult, but I knew it had to be done.

Orders poured in, we processed and forwarded them to Paul, and Vicki even pitched in to help with the foreign mail. That was something she had done often over the years; it was our little joke: this was her “salary.” Some foreign customers paid by International Money Order, most with cash. Sometimes it was currency from that country, usually greenbacks. Vicki got to keep the cash. No big deal, not to me. However, when processing the initial surge of orders for new releases, many foreign dealers also paid cash. Hefty amounts arrived Registered Mail, and I sometimes winced when I handed the day’s stack to Vicki, knowing that there was two or three thousand dollars in those envelopes. That was the deal, I couldn’t complain. One thing for sure, Vicki never bugged me for money to buy clothes.

In the fall of 1980 Paul was shopping in one of the large malls in the Baltimore suburbs. What prompted him to look in the Elvis section in the record department at Hutzler’s he isn’t sure; a major department store would never have anything other than the standard RCA releases. They didn’t carry imports; even if they had, the chance of them having something Paul needed for his collection was negligible. Chalk it up to an Elvis fan’s self–indulgence, thumbing through the unmatchable body of work that provided countless hours of pleasure. What he found was, in Paul’s words, “A shock.” “I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. The Elvis section was massive. They had multiple copies of every one of our albums. There was at least three of every title. The double albums and the box set filled almost an entire row. There must have been ten of each one. I thought to myself, ‘Oh, oh, we don’t need this kind of exposure. If this store has our albums, does the entire chain carry them?’”

Paul’s next stop was Dillard’s, a major department store chain in the southeast. The scene was repeated; the Elvis section was overflowing with our titles; the same was true at Macy’s. Paul remembered my mentioning that a new customer in South Carolina had been ordering our albums in lots of 100 and more of every title. This had to be where they were winding up. Just how many more major chains were now carrying our records? This was the kind of success we once dreamed of; it was now too much of a good thing. Were our albums now in chain record stores and department stores nationwide? If not, would they soon be?

Paul called me with the news; I hurried around to all the big stores in the Glendale Galleria and other malls in the area. I checked The Wherehouse, Licorice Pizza, Tower Records, and Music Plus, the four largest record chains in California. None of them had our albums. Not yet. Was it just a matter of time? What to do? I had to contact the dealer in South Carolina and find out just how extensive his distribution was and what other chains now carried our LPs. I had just last week shipped him over one thousand albums. I imagined he had tapped an overseas source; that seemed the most likely destination for the quantities he ordered. That they would be distributed domestically, and to major chains to boot (love that word), never occurred to me. As it turned out, we didn’t have to worry about it for long.

Vic was riding high, that first flurry of orders for the “Million Dollar Quartet” and “The ’68 Comeback Vol. 2” was more than we expected. Our core mailing list, those who had previously ordered, was over ten thousand; we had dealers, large and small, gobbling up catalogue albums, and ordering double the previous quantity for new releases. Vicki was especially pleased; she said something about nice presents for her friends back in Philadelphia. Speaking of presents, 1980 was the Christmas Vicki was up until almost dawn getting everything wrapped; I conked out between two and three in the morning. Patrick had them all opened before we got up, every last one of them.